What is a Low Pressure Sensor

Low pressure sensors are precision pressure measurement instruments designed specifically to detect minute pressure fluctuations, typically operating within a range of 0–1 mbar (100 Pa) to 0–1000 mbar.

Unlike hydraulic sensors handling thousands of pounds per square inch (PSI) of high pressure, these devices rely on highly sensitive diaphragms to capture minute variations in air or gas pressure. Whether you require low-pressure sensors for medical ventilators or differential pressure sensors for HVAC ducting, understanding the fundamental principles is the first step towards obtaining accurate data.

Basic Structure of Low Pressure Pressure Sensors

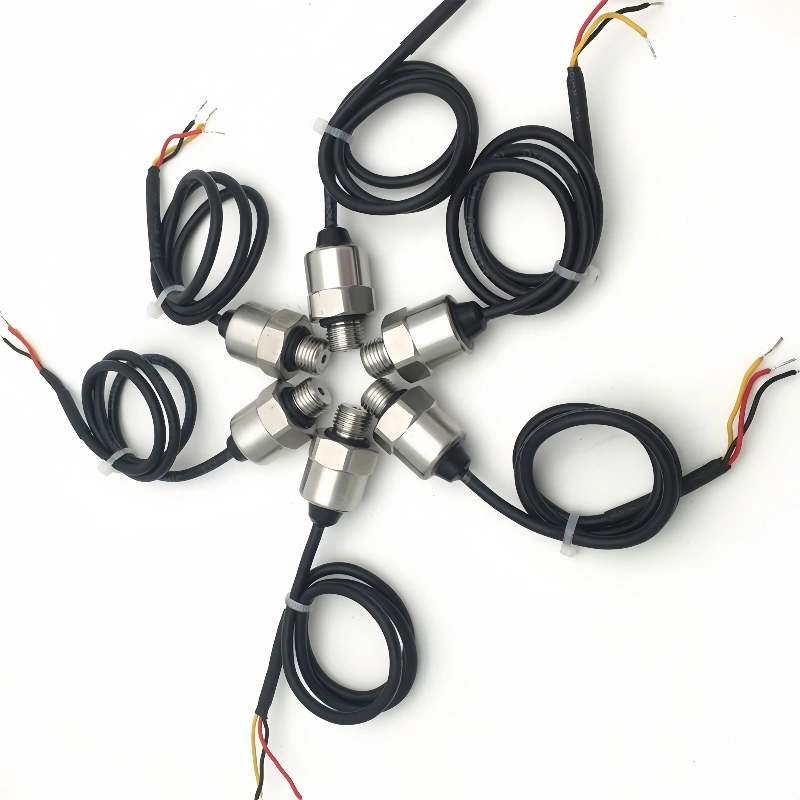

Low-pressure pressure sensors typically comprise a pressure-sensitive element, signal processing circuitry, and an output interface. Their core component consists of a sensing element (usually a piezoresistive pressure sensor or capacitive chip) and a micro-machined diaphragm. In low-pressure devices, this diaphragm is exceptionally thin, enabling detection of even the most minute deformations. This mechanical movement is subsequently converted into an electrical signal output via signal conditioning circuitry.

Working Principle of Low-Pressure Sensors

Among common low-pressure sensors, the operating principles of pressure-sensitive elements vary considerably, encompassing diaphragm-type, resistive strain-gauge, and capacitive designs.

Resistive pressure sensors employ strain gauges, typically comprising a metal bending film or grid structure mounted within the sensor’s pressure measurement chamber. When medium pressure acts upon the sensor housing or chamber, the bending film or grid structure undergoes minute deformation.

This deformation causes a change in the resistance value of the sensing element, known as the resistive strain effect. The sensor measures this change in resistance and converts it into a corresponding electrical signal.

Capacitive pressure sensors reflect pressure changes by measuring variations in capacitance between two capacitor plates. One plate is fixed to the deformable side of the elastic element, while the other is mounted on the non-pressurised surface.

Characteristics of Low Pressure Pressure Sensors

The resistance value changes measured by low-pressure sensors may be extremely minute, necessitating signal processing to convert the faint raw signal into a stable, clean, usable signal.

The output from low-pressure sensors (such as miniature strain gauges or microcapacitors) is often only in the millivolt range. Consequently, a high-input impedance, low-noise, low-temperature-drift instrumentation amplifier is first required to amplify the signal to a standard voltage range, such as 0-5V.

Signal processing circuits typically incorporate components such as amplifiers, filters, and analogue-to-digital converters. These transform minute resistive variations into more substantial voltage or current signals, subsequently converting them into digital form for processing and transmission.

Signal Output of Low Pressure Pressure Sensors

Low-pressure sensors may output either analogue signals (such as voltage or current) or digital signals (such as digital communication protocols). These signals can be connected to control systems, data acquisition equipment, or displays for real-time monitoring, control, and recording of pressure data.

Analogue Signal Output

Voltage Output Type:

Characteristics: Output voltage is directly proportional to measured pressure.

Advantages: Simple circuitry, easily integrated into existing systems.

Current Output Type:

Characteristics: Typically employs a 4-20mA standard signal, with output current exhibiting a linear relationship to measured pressure.

Advantages: Strong resistance to interference, capable of long-distance transmission, and less susceptible to line resistance effects.

Digital Signal Output

Serial Communication Interfaces:

Such as RS-232, RS-485, USB, etc.

Characteristics: Transmits data via serial communication protocols, enabling long-distance, multi-parameter transmission.

Advantages: Rapid data transmission, robust interference resistance, facilitates intelligent management implementation.

I²C/SPI Interface:

I²C (Inter-Integrated Circuit) and SPI (Serial Peripheral Interface) are two common short-range communication protocols.

Characteristics: High transmission rates, convenient connectivity, suitable for data exchange between microcontrollers and sensors.

Advantages: Conserves pin resources, simplifies circuit design.

Practical Applications of Low Pressure Sensors

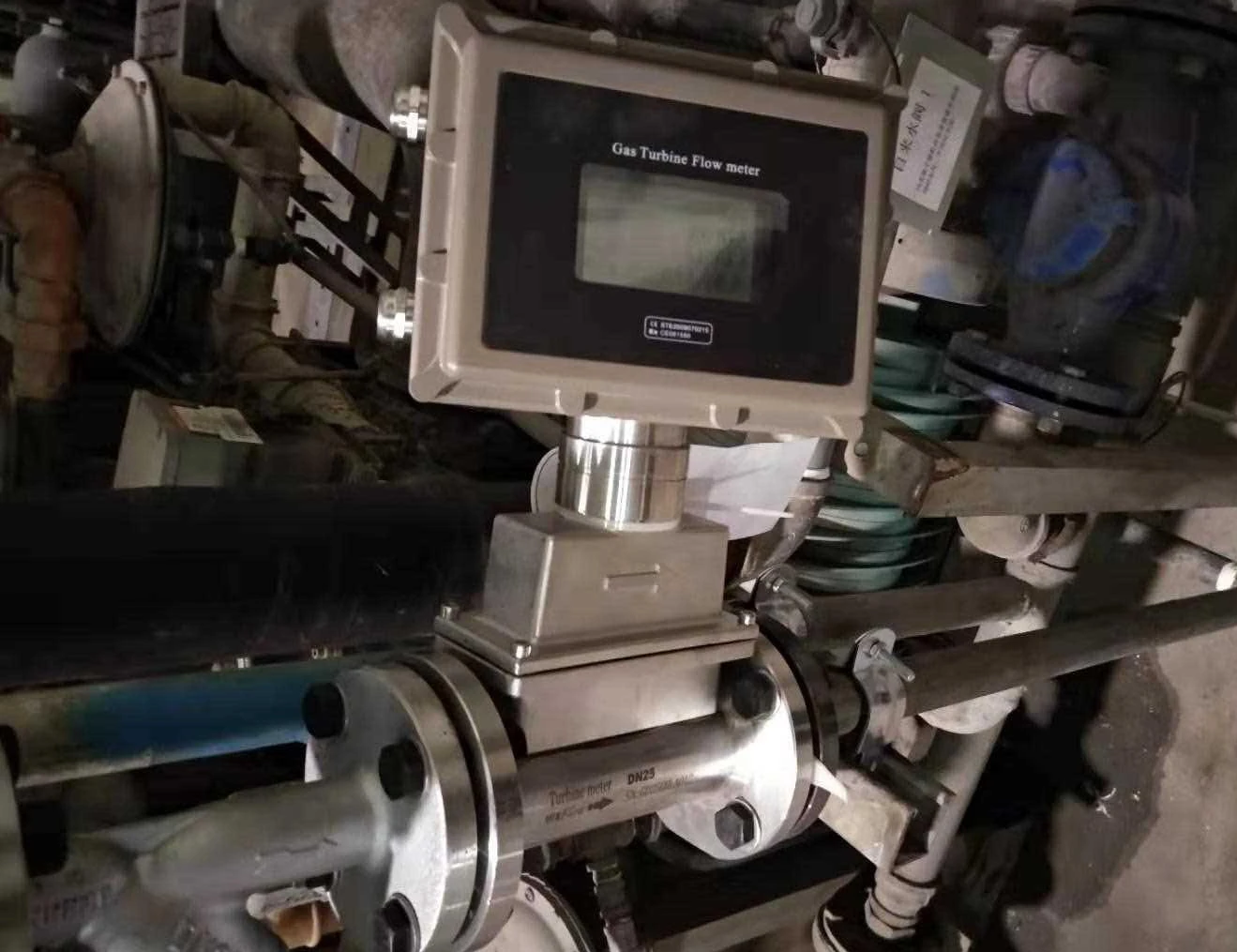

1.Industrial sector:Low-pressure pressure sensors are extensively employed in industrial systems such as compressed air systems, water supply and drainage systems, refrigeration systems, and pressurisation systems.

2.Medical sector:Low-pressure pressure sensors are widely utilised in medical devices including ventilators, sphygmomanometers, and infusion pumps.

3.Automotive sector:Low-pressure pressure sensors are extensively applied in automotive powertrain systems, air conditioning systems, and braking systems.

4.Environmental Protection Sector:Low-pressure pressure sensors are extensively employed in environmental protection equipment, including flue gas emission monitoring and water quality monitoring systems.

How to Select the Appropriate Pressure Sensor

1. Identify the type of pressure being measured

Positive pressure scenarios: Where the measured pressure consistently exceeds atmospheric pressure (e.g., pipeline pressure), either gauge pressure or absolute pressure transmitters may be selected (determining whether atmospheric pressure reference is required depends on system specifications).

Negative pressure scenarios: Where the measured pressure may fall below atmospheric pressure (e.g., vacuum pump outlet), either a gauge pressure transmitter (where readings may be negative) or an absolute pressure transmitter (where readings remain positive) must be employed.

Vacuum scenarios: Where absolute vacuum levels must be measured (e.g., semiconductor manufacturing vacuum chambers), an absolute pressure transmitter is mandatory (typically with a 0-1 bar absolute pressure range).

2. Measurement Range and Accuracy Requirements

Selection must ensure the sensor’s range covers the actual operating pressure with sufficient margin (typically 1.5 times the maximum working pressure). An insufficient range risks sensor overload damage, while an excessively large range compromises measurement accuracy.

Accuracy is another critical metric, typically expressed as a percentage of full scale (FS). Industrial applications vary significantly in accuracy requirements:

General industrial control: ±1% FS or lower accuracy suffices

Process control: Typically requires ±0.5% FS

Precision measurement: May necessitate ±0.1% FS or higher

2. Medium Compatibility

Compatibility between the pressure sensor and the measured medium is paramount, requiring consideration of:

Wetted materials: Components in contact with the medium must resist corrosion. Common materials include stainless steel, Hastelloy, and titanium; specialised selections are required for aggressive media (e.g., strong acids/alkalis).

Sealing methods: Different seal materials (e.g., fluorocarbon rubber, PTFE) suit varying media and temperature conditions.

Cleaning requirements: Food and pharmaceutical industries demand hygienic designs to prevent contamination.

3. Environmental Conditions

Industrial environments are often complex and variable, necessitating consideration of the following factors:

Temperature Range: Includes both ambient operating temperature and medium temperature. Exceeding the sensor’s rated temperature range will compromise performance and lifespan.

Humidity: High-humidity environments require sensors with high ingress protection ratings to prevent moisture ingress.

Vibration and Shock: Applications involving heavy machinery or vehicles necessitate models with robust vibration and shock resistance.

Explosion-proof requirements: Hazardous areas in petroleum, chemical, and similar industries necessitate products meeting corresponding explosion-proof ratings.

4. Electrical Characteristics and Interfaces

Power supply requirements: Different sensors have varying power supply needs (e.g., 12VDC, 24VDC), which must match the system.

Output signal: Select analogue or digital output based on the control system, ensuring signal type compatibility with receiving equipment.

Electrical connection: Consider factors such as connector type, protection rating, and cable length.

5. Long-Term Stability and Reliability

Industrial applications often demand sensors capable of sustained, stable operation over extended periods.

Key considerations include:

Long-Term Stability: Typically expressed as annual drift rate; high-quality sensors achieve ±0.1% FS/year.

Calibration Interval: Determine whether periodic calibration is required based on application needs, alongside assessing calibration convenience.

FAQ

Pressure Rating Classification

Low Pressure

Generally, the defining value for low pressure may vary depending on the application field, but typically falls between 0.1 MPa (megapascals) and 1.6 MPa. In certain specific circumstances, such as pneumatic or hydraulic systems, the definition of low pressure may be more precise, for example below 0.7 MPa.

Medium Pressure

The defining values for medium pressure also vary by specific application, but are generally considered to lie between 1.6 MPa and 10 MPa. This range ensures medium pressure’s broad applicability across multiple fields.

High Pressure

High pressure is typically defined as ranging from 10 MPa to 100 MPa. This high-pressure range can generate greater pressure and energy density, making it suitable for applications requiring elevated pressure levels.

Ultra-High Pressure

Ultra-high pressure is generally defined as exceeding 100 MPa, sometimes reaching thousands of MPa (i.e., the GPa level). Such extreme pressures typically necessitate specialised equipment and materials capable of withstanding these conditions.

How to maintain pressure transmitters?

Maintaining pressure transmitters is crucial for ensuring their long-term stable operation:

1.Regularly inspect wiring and connection ports to ensure no loose or corroded components.

2.Calibrate periodically to guarantee reading accuracy.

3.Clean the transmitter surface to prevent dust and grime from affecting performance.

4.Document each maintenance session to track equipment condition.

What is the difference between a low-pressure sensor and a vacuum sensor?

The key lies in the reference point. Low-pressure sensors typically measure small positive pressures above atmospheric pressure (e.g., 0 to 50 millibars). Vacuum pressure sensors, however, measure pressures below atmospheric pressure (negative pressure). Although the two technologies are similar, they are calibrated differently to ensure accuracy within their respective specific ranges.

Can low-pressure sensors measure negative pressure?

Yes, certainly. Many of our sensors are “composite” or bidirectional. This is crucial for applications such as hospital isolation wards or cleanrooms, where you may need to monitor subtle positive and negative airflows. Should you require a sensor with a pressure range spanning negative to positive values (e.g., -500 Pa to +500 Pa), please let us know; we frequently configure such sensors.

We steadfastly uphold reliable quality as our cornerstone, continuously optimising product performance to proactively address our users’ evolving application requirements. Through streamlined operational procedures and a comprehensive service framework, we are committed to providing robust technical support and sustainable solutions for clients across diverse industries, thereby empowering secure and efficient industrial development.